Oyster farm archives, 2023

Story from a Fluid Field by Fine Brendtner

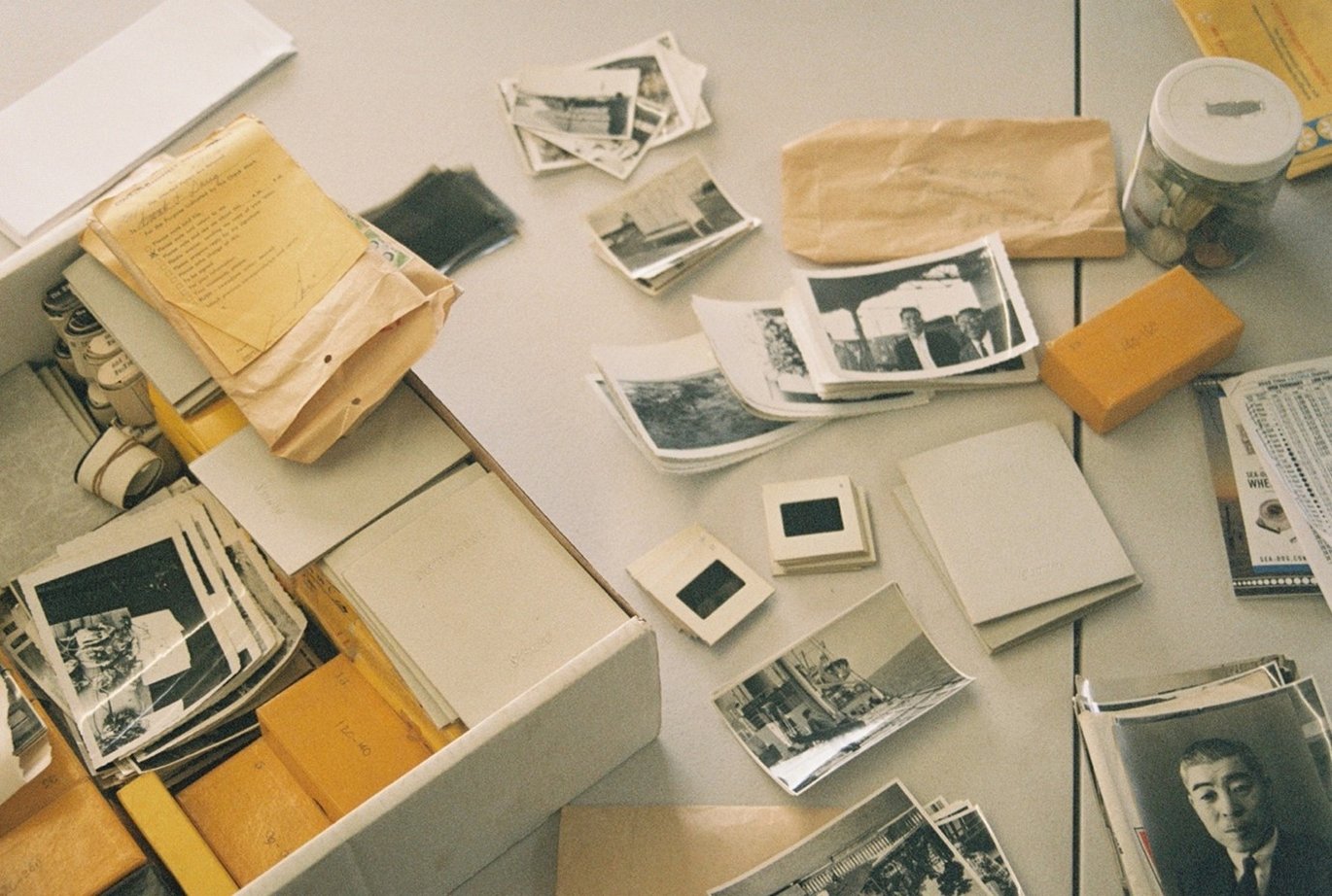

A treasure trove of images narrating an environmental history that spans across the Pacific Ocean, was the last thing I had expected to find on my day at the oyster farm headquarters in Nahcotta. Yet, there it was, stored away in filing cabinets and corners of the otherwise sparse and drafty rooms: a rich collection of black and white film, photographs, maps, tintypes, slides, and postcards. What bigger picture might the sum of these images reveal? Puzzled together, they form a surprising insight into entwined human and oyster lives at the US Pacific Northwest coast and beyond.

~ ~ ~

Hospitality must be written in capital letters when it is used to describe the sentiment harbored by Nahcotta's tight-nit shellfish farming community. A few hours after I stepped into Jeff's office to introduce myself, he clears a desk for my research and I sit down, a mug of coffee steaming to my right and the image archive sprawled out in front. Jeff took the morning to share his story of working with oysters and that of those who came before him. As the manager of Nahcotta's Pacific Coast Shellfish farm he is busy and has a schedule ruled by the tides. Now it is noon and as the high tide nears its peak the oysters are fully submerged by water and off limits, so he readies himself for a lunch break. Was there anything else I needed?, he asks before leaving. Fanta, Cola, some type of food? Oh, and in case I was gone before his return, I should come back the next morning around seven am for a walk on the oyster beds while the tide was out.

Slightly perplexed at the sudden stroke of fortune, I sit and peek at the past of a place I have only stepped foot on for the first time this morning. This is a type of vernacular archive, an oyster farmer's story in pictures, a personal collection carefully curated and preserved by his successors. As I will find out along the way, residents of Nahcotta, the small coastal town nestled between Washington's Willapa Bay and the Pacific Ocean, are exceptional in keeping records of their rich oyster histories; and oyster histories, there are many.

People have been growing shellfish in Willapa Bay for generations, with some family members being amongst the first European settlers in the area during the 1850s. Before then, Chinookan, Lower Chehalis and Quinault peoples used to harvest shellfish, mainly cockles, wild Olympia oysters (ostrea lurida) and clams, in what was then called Shoalwater Bay. They were the initial guardians of the bay and the ones who showed these 'shellfish gardens' to Lewis & Clarke around 1805, an encounter that marked the beginning of the "Shoalwater Bay trade". At the height of San Francisco's gold rush, an emerging gourmet culture made the European settler's oyster trade along the Pacific West Coast lucrative enough for Willapa Bay to become the wealthiest region in Washington for a while during the 1850s and 1860s. Oysters at that time gathered a symbolic meaning for those who could acquire them. A new demand and market for Shoalwater Bay oysters brought prosperity to oyster farmers, yet it fractured Chinookan and Chehalis livelihoods and caused the native oysters to decline.

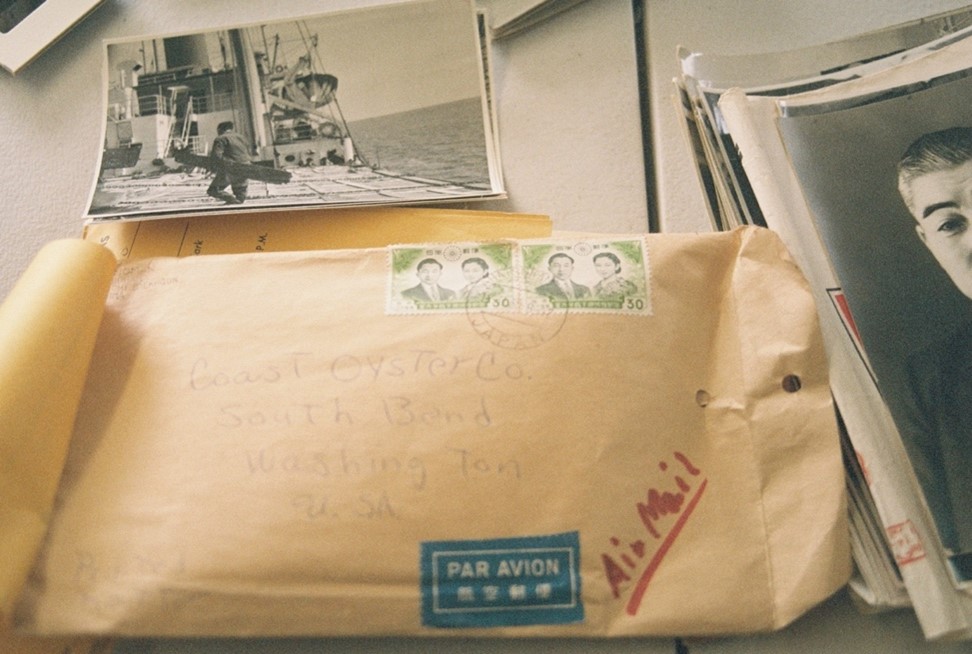

When the Olympia oyster population shrank, Willapa oystermen responded by cultivating areas that were not natural oyster beds. Following a rich trading history and cultural exchange between Japan and the United States before and after World War Two, Willapa's oyster farmers began to import spat (read: baby oysters), from Hiroshima Bay.

They thereby introduced an oyster native to the Asian Pacific Coast, the Pacific oyster (magallana gigas), to the US Pacific Coast.

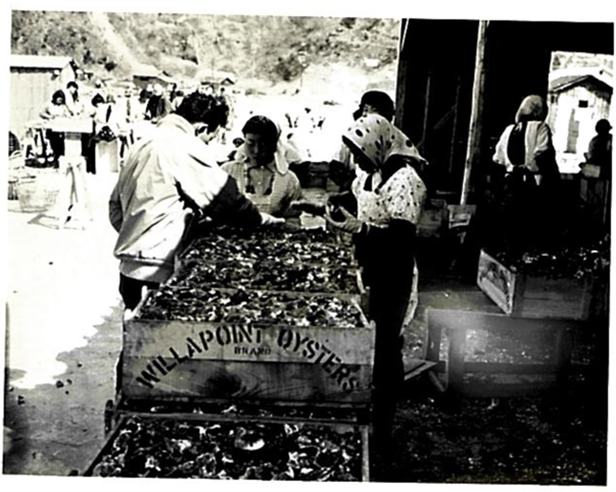

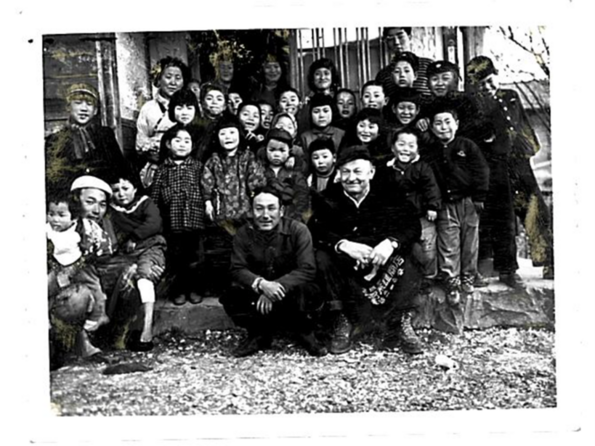

I examine the pictures in front of me, one at a time. Each of them ignites a curiosity, sparking questions that lead to more questions. What stands out are the rolls of film, slides and letters that memorialize E. H. Bendiksen´s visit to Japan in the early 1960s. Bendiksen was among the first growers, alongside the Wiegardt and Hilton family, to start a shellfish enterprise that would ship oysters around the nation and across the world.

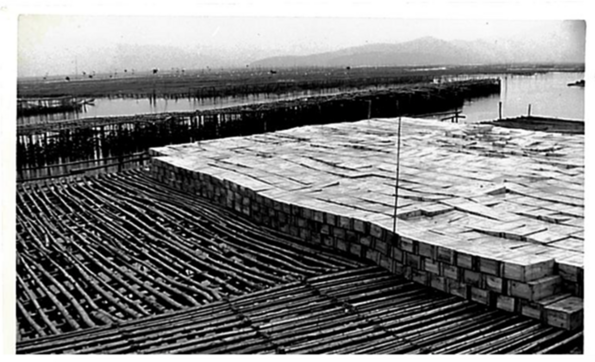

These pictures tell that tale. They show hundreds of wooden boxes with the label "Willapoint Oysters". Filled to the brim with seeded oysters, the crates await their voyage across the Pacific. Other pictures show Bendiksen crouching among a group of children and adults. They capture a sentiment of the more-than-business trip and form part of his documented fascination with Japan's local oyster culture.

With the advent of hatchery technology in the 1970s, the oyster spat trade slowly came to a halt. The Pacific oyster was now bred locally and had become naturalized in Willapa Bay's waters. While the native Olympia oysters had already been under pressure from overfishing, they were now outcompeted by the introduced species altogether. Today, Pacific oysters account for most of Willapa's commercial harvest.

By the time I emerge from the travel through the archive, I am captured by the curious history of oysters and the people that harvest them. A parallel world of intimate connections between waters, mollusks and human histories has become palpable. When in 2007 ocean acidification hit this region's oyster hatcheries and killed billions of oyster larvae overnight, it threatened to wipe out not only the livelihoods of people growing shellfish, but an entire culture and environmental history attached to it.

As I walk from the office to my car, Phil from the shellfish farm next door comes running towards me. He heard that I will be joining Jeff on the oyster beds tomorrow. I best be prepared, he says, as he hands me a pair of gloves and rubber boots in the perfect size. "See you tomorrow. Let me know if you need anything!"