Drawings of a reef otherwise, 2024

Story from a Fluid Field by Nils Bubandt

The coral reefs of Raja Ampat on which I do fieldwork are not just a site of record-breaking biodiversity. They are also a crowded spiritscape. People in Raja Ampat tell me that many kinds of beings besides invertebrates, coral polyps, fish, and turtles inhabit these coral reefs. Let me, for want of a better word, call these beings "meta-humans": human-like ephemeral figures who can take many forms, including the form of underwater animals of various kinds.

One of the methods through which I have been trying to undertake fieldwork about these meta-humans on the reefs of Raja Ampat is through drawings. One might perhaps call this method "drawing elicitation". The particular drawings that I work with have a fascinating provenance. They were produced, probably in the 1930s, by so-called snon mon, people with shamanic abilities to ”see” into the world of these meta-humans. The meta-humans have many names. One of them is mon.

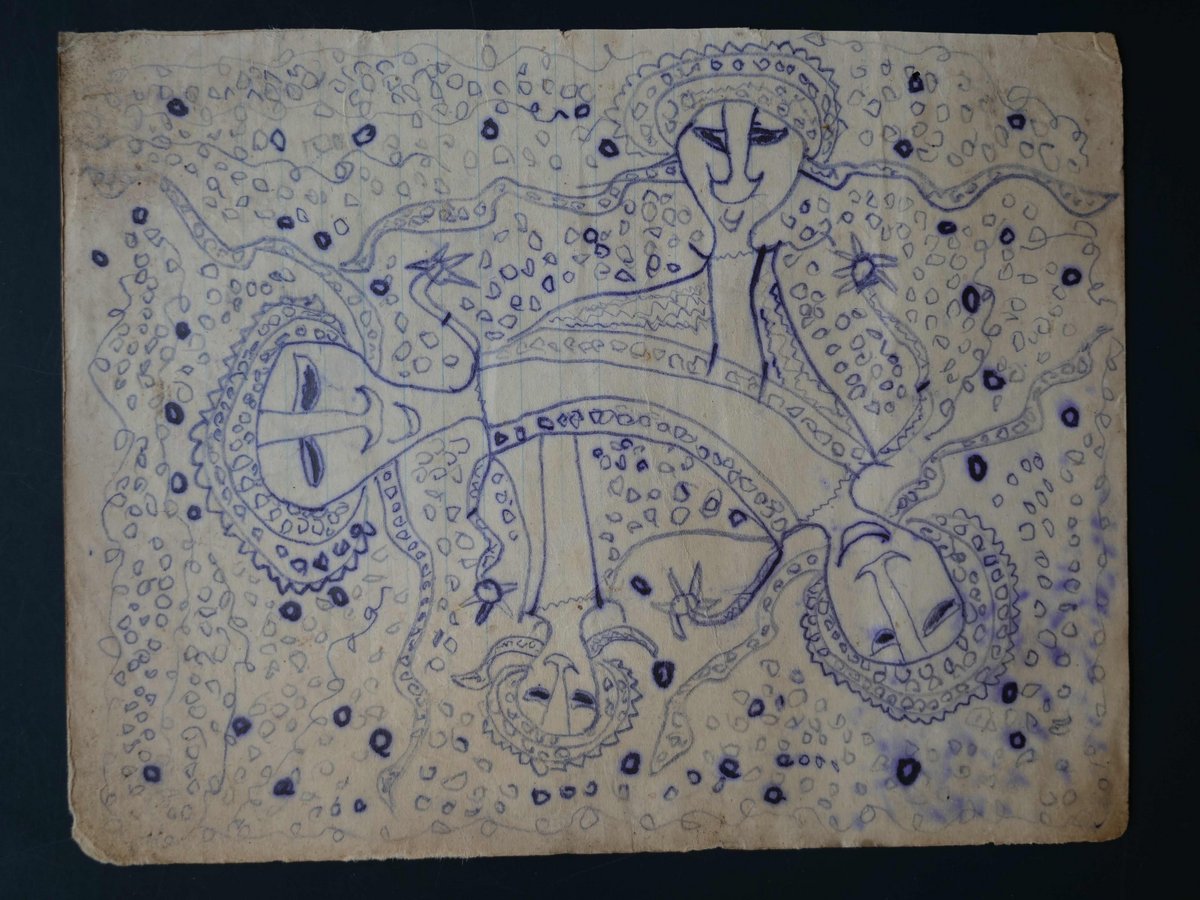

The mon drawings are spectacular by any artistic standard. They are intricate, elaborate, and evocative. They are also eerie because they portray what looks like recognisable landscapes or seascapes but these scenes are inhabited by strange-looking beings, the meta-humans as the snon mon would see them on their dream travels.

The mon drawings were collected by Freerk Kamma, a long-term missionary to and later anthropologist in West Papua. But they were long thought to have been destroyed by the Japanese during World War II. I encountered some two hundred of these drawings in a Dutch archive in 2018 following the lead of Raymond Corbey who had featured a few drawings in a wonderful book about ritual art in Raja Ampat. The discovery of the drawings was a revelation, but also a conundrum. They were undescribed and unorganized in the archive. Kamma repeatedly stated his intention to analyse and describe them in full but never managed to do so before he died in 1987.

I decided to turn the mon drawings into a methodological opportunity. On every fieldwork trip since 2018, I have spent hours in in numerous coastal villages across Raja Ampat showing these drawings to people who know about the world of mon. Today, most of these people reject the term snon mon to describe themselves. To the Biak-speaking people of Raja Ampat today, the term has a negative meaning. The Christian mission in West Papua, headed for many years by Kamma, demonised the snon mon as sorcerers and icons of pagan superstition. Indeed, the drawings were surrendered to Kamma in the 1940s as proof that the "shaman-sorcerers" had now become faithful Christians. The mon drawings are in that sense both ethnographic objects and evidence of a Christian-colonial epistemicide (the evisceration of an Indigenous epistemology or world view).

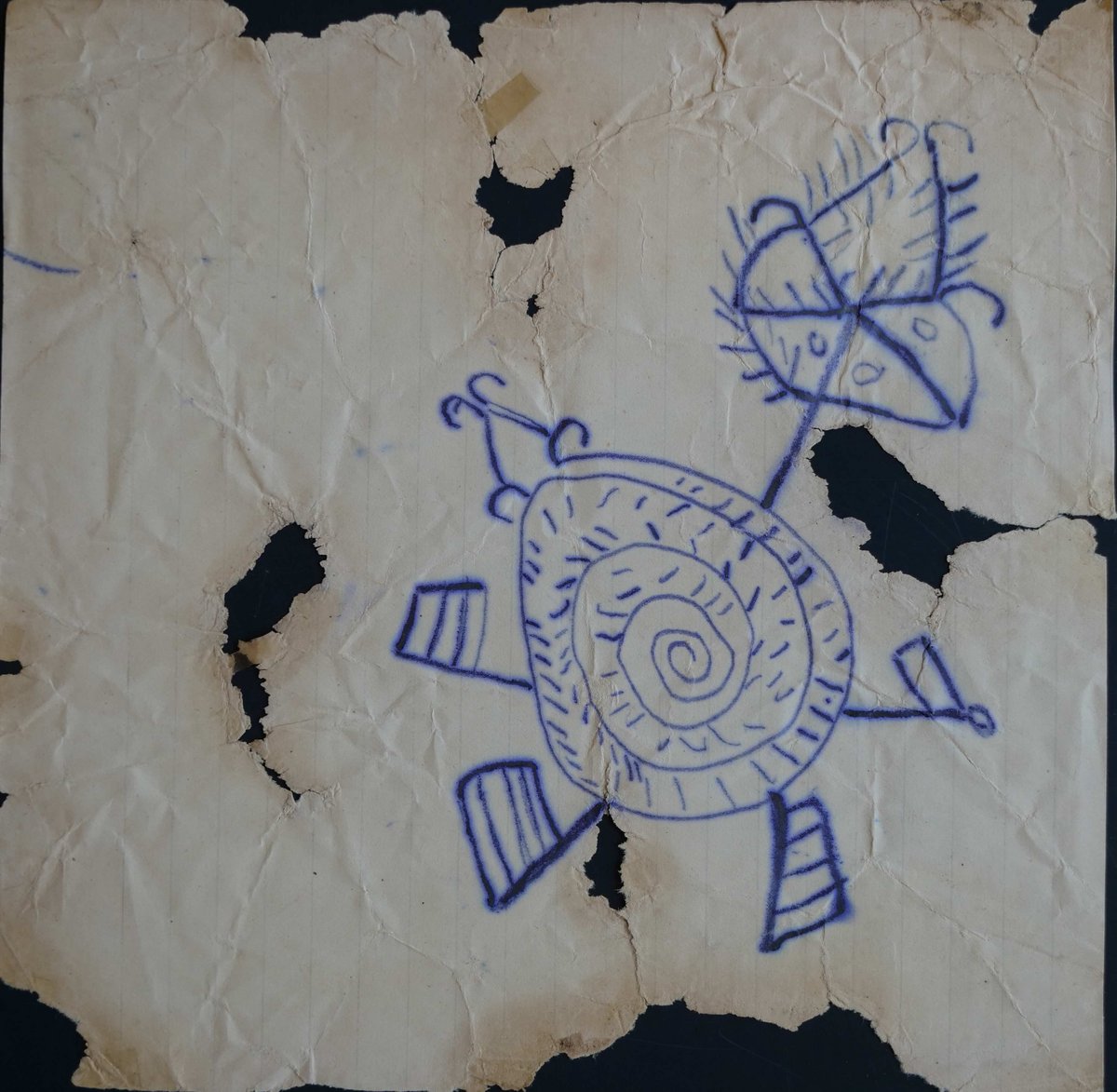

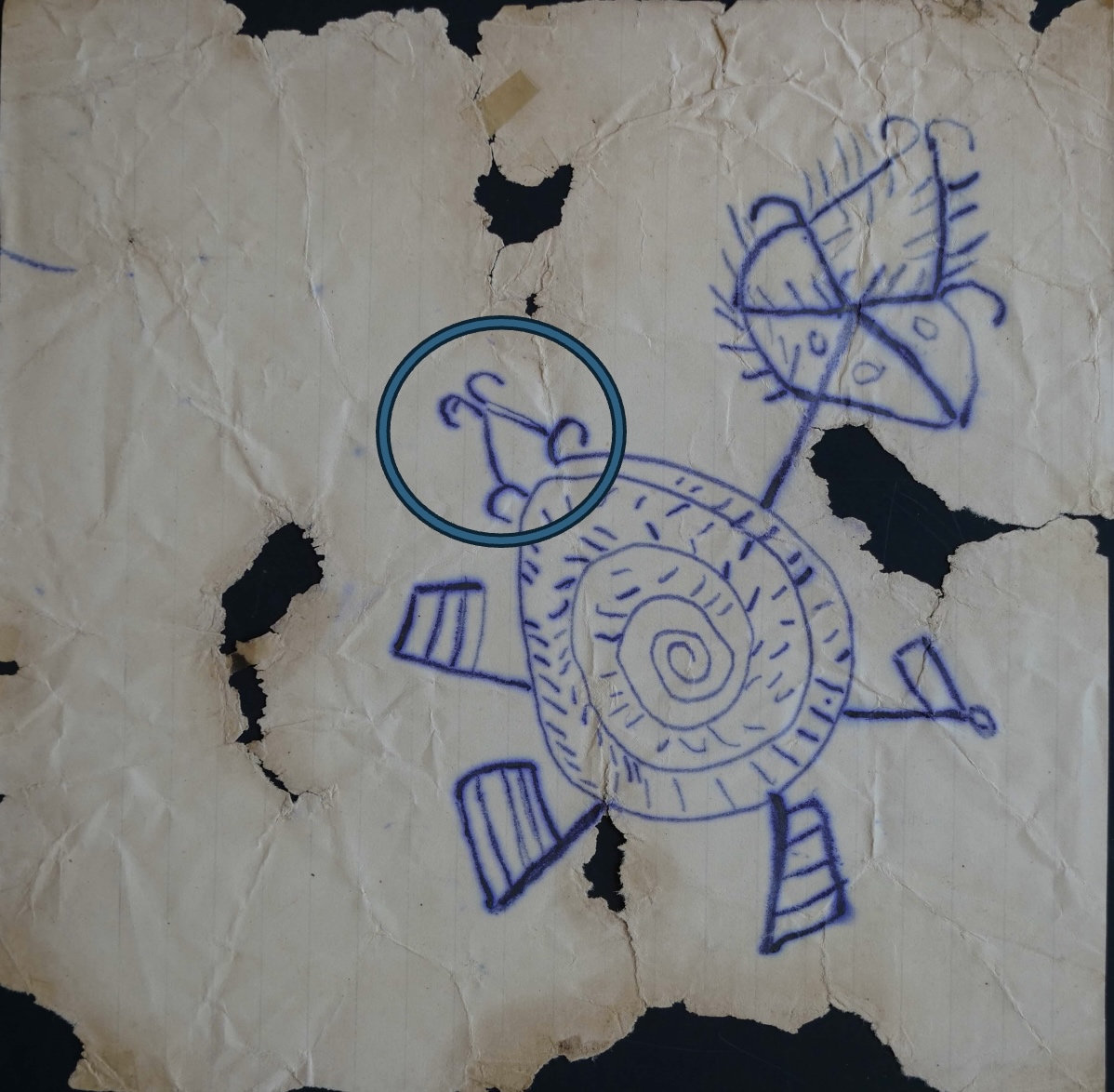

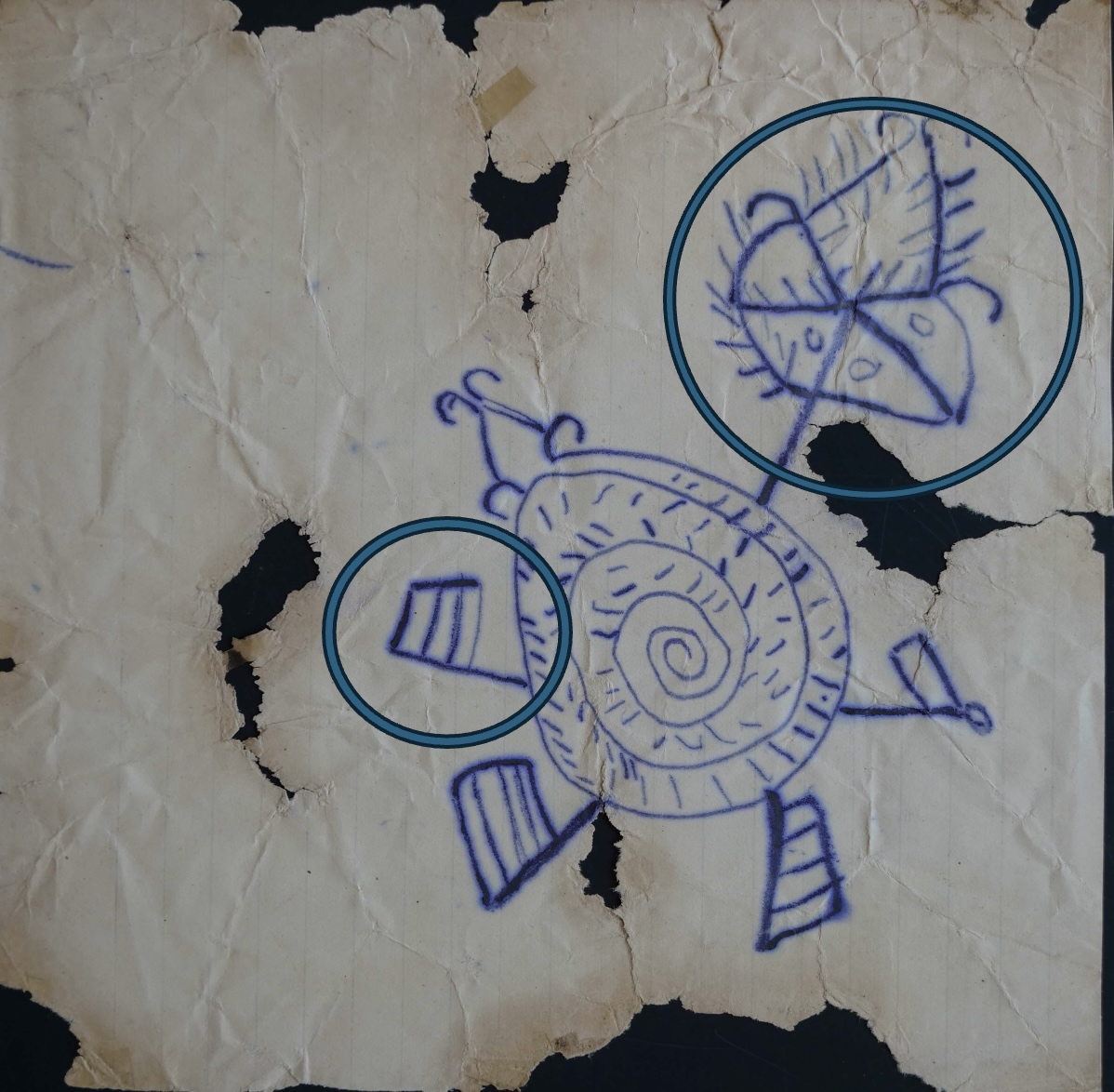

In spite of the demonisation of the snon mon, it is to people with the ability to see and travel into the world of the mon that villagers in Raja Ampat turn when they are ill, have birthing problems, or experience other misfortune, and most villages is home to at least one of these knowledgeable people. Listening to their interpretations of the old drawings has become an important methodological pathway into the world of meta-humans that has also helped me see coral reefs otherwise. The reef world of Raja Ampat, as it turns out, is as crowded by meta-humans as it is rich in underwater biodiversity. Let me give just two examples of this meta-human diversity. Take this drawing.

At first glance, this mon drawing looks like an oddly adorned spiralling shell. I was told the spiral creature is a korkór, a chambered nautilus shell (Nautilus pompilius). But that, too, is not entirely correct because this is not a drawing of an ordinary shell. The adornments, as only a snon mon can see them during his or her dream travels (called datutér), are indications that this particular chambered nautilus is the dwelling place of meta-humans. This particular dwelling, I was told, is the “spirit castle” of a meta-human called baradota. The baradota is considered extremely dangerous. Its punishment is deadly because it takes spiritual revenge for wawír, one of the most terrible of crimes. Wawír refers to incest, which in this part of the world means sexual relations between people who are closer than fourth-degree cousins. In the darkness between houses or in garden plots not all young people have a clear sense of all their third-degree cousins. Romance, illness, and metahumans are therefore bed-fellows.

In the reality that one enters during dream travel, the spiraling structure of the baradota dwelling is a complex maze in which the witch spirit hides the soul (rúr) of the person who is guilty of incest and who now lies sick back in the village. It is the task of the snon mon on his or her dream travels to enter the shell structure and negotiate with the witch spirit for the release of the soul of the patient in order to bring it back to the village. This is a difficult and dangerous task. The naive dream traveller, I was told, might be tempted to enter through what looks like a door at the entrance in the top left corner of the drawing. But the entrance of this "door" are actually fish hooks designed to catch intruders.

The wise dream traveller will instead enter through the large round bulb in the top right corner, which my interlocutors called the "head" (kepala) of the dwelling. The “head” is the seat of power. The word people would use for this seat of power is the Indonesian term benteng, which literally means “fortress”. The flags that protect the bottom half of the spirit dwelling are also fortresses, magical forms of powerful protection. If a dream traveller has insufficient spiritual power (called nanek) of his or her own to outsmart or defeat the witch occupant of this castle, the dream traveller will also be trapped and held hostage in the fortified shell of the witch.

The world of witch spirits and other meta-humans is cosmo-political: it speaks to a politics that both mirrors and exceeds the world of politics as humans know it. Meta-humans, for instance, live in castles, as did the sultan of Tidore who used to rule over this part of Papua. The Papuan subjects of the sultan would undertake dangerous sea journeys to Tidore to pay tribute of sago and sea products but would return with titles and spiritual power (nanek). These tribute journeys to the sultan mirror the dream voyges that the snon mon of the olden days, and their nameless successors today, undertake to reach the underwater realm of meta-humans. Cosmo-politics also takes another form in the drawing. Benteng, the Indonesian word for castle or fortress, besides referring to magical forms of protection also describes the colonial structures that Spanish, Portuguese, and Dutch colonizers have built in this part of Indonesia for centuries. With this in mind, now take another look at the flags that magically protect the spirit dwelling in this drawing: they have horizontal stripes, some of them mirroring exactly the horizontal tricolour of red, white, and blue in the Dutch national flag. Reading the drawing “cosmopolitically” with the help of people with insight into the world of meta-humans allows us a glimpse into a meta-human coral world in which figures that at first glance look like animals are very much human-like. Their magic, moreover, harnesses the power of colonialism.

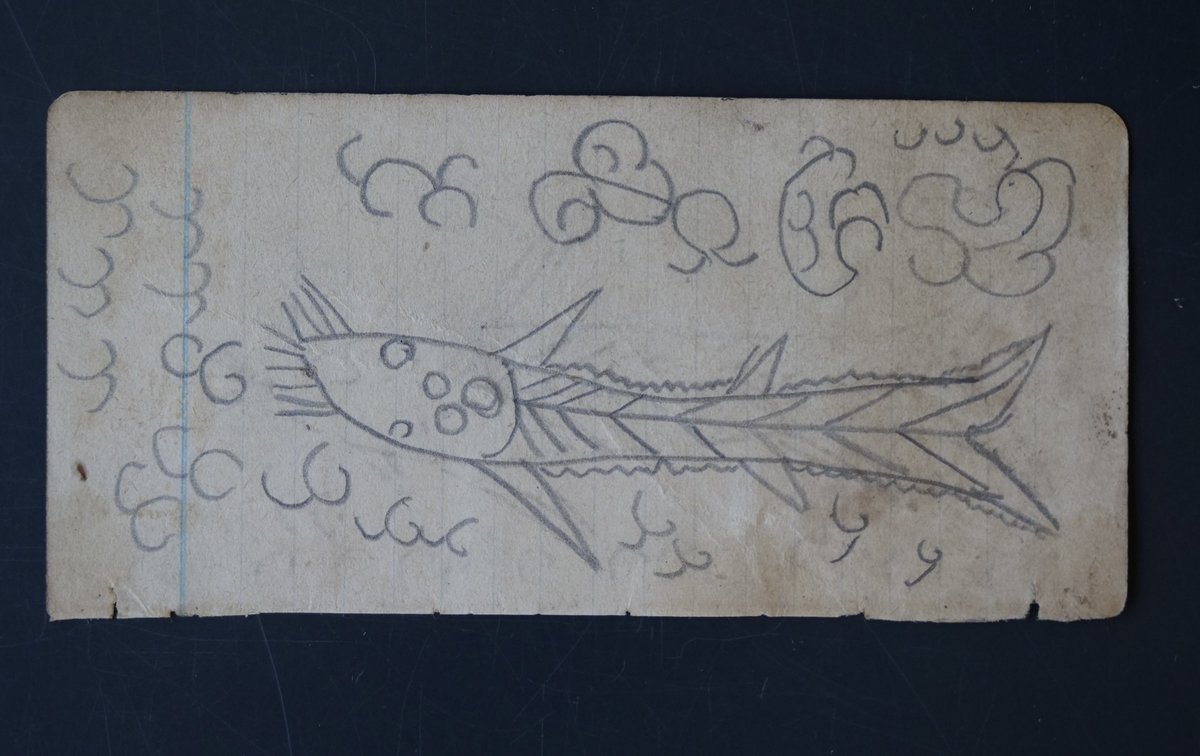

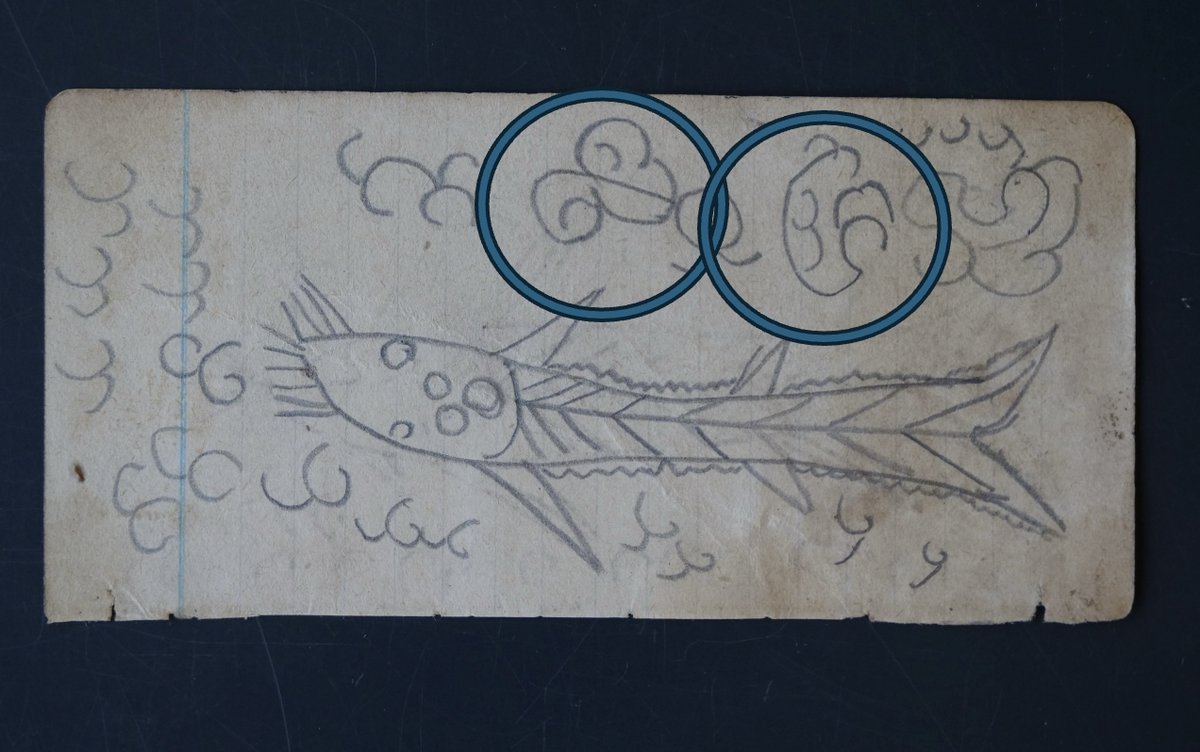

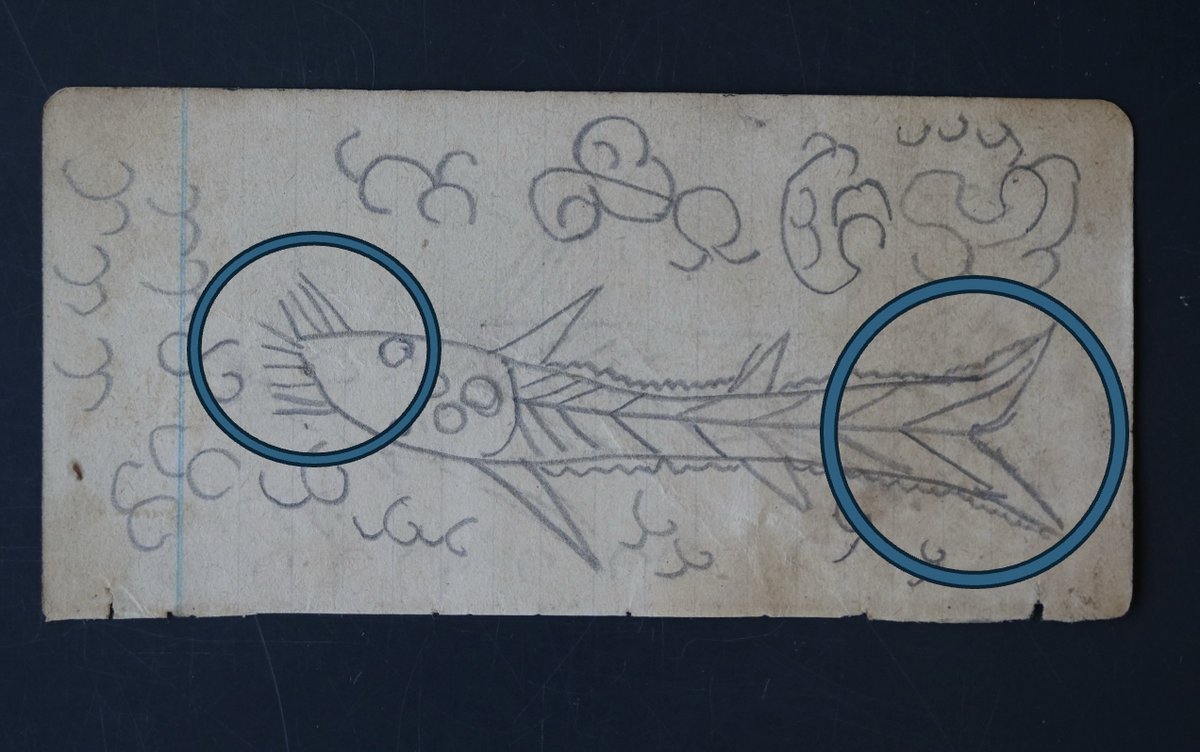

The mon drawings – when read carefully – tell underwater stories not only of politics however. They also tell stories full of intimate insight into natural history. Take this second drawing.

This drawing, I was told, depicts a manwén torén, a sea witch. The witch has a human form but is often disguised as an animal. In this case, the witch is disguised as a fish known in the local dialect of the Biak language spoken in Raja Ampat as inbeyaoyék. One can tell it is not an ordinary fish, however, because it has five eyes. I was told that people with ill-will towards other villagers will seek out this meta-human creature and make an offering to it before throwing an old piece of clothes - preferably an undergarment or loin cloth - of the person they want to harm into the coral reef where the inbeyaoyék sea witch dwells. A person with such ill-intent will look for the dwelling place of the sea witch by looking for the tatóm that protect it. Tatóm are algae that grows in clumps resembling dark tufts of hair on the sea bed. They are the magical protection, the fortress, of the sea witch.

Once sorcerized by the sea witch, the genitals of its human victim will immediately begin to itch and swell. A dream traveller who seeks to cure the genital swelling caused by a sea witch will have to seek out the sea witch on a dream journey and negotiate for it to stop.

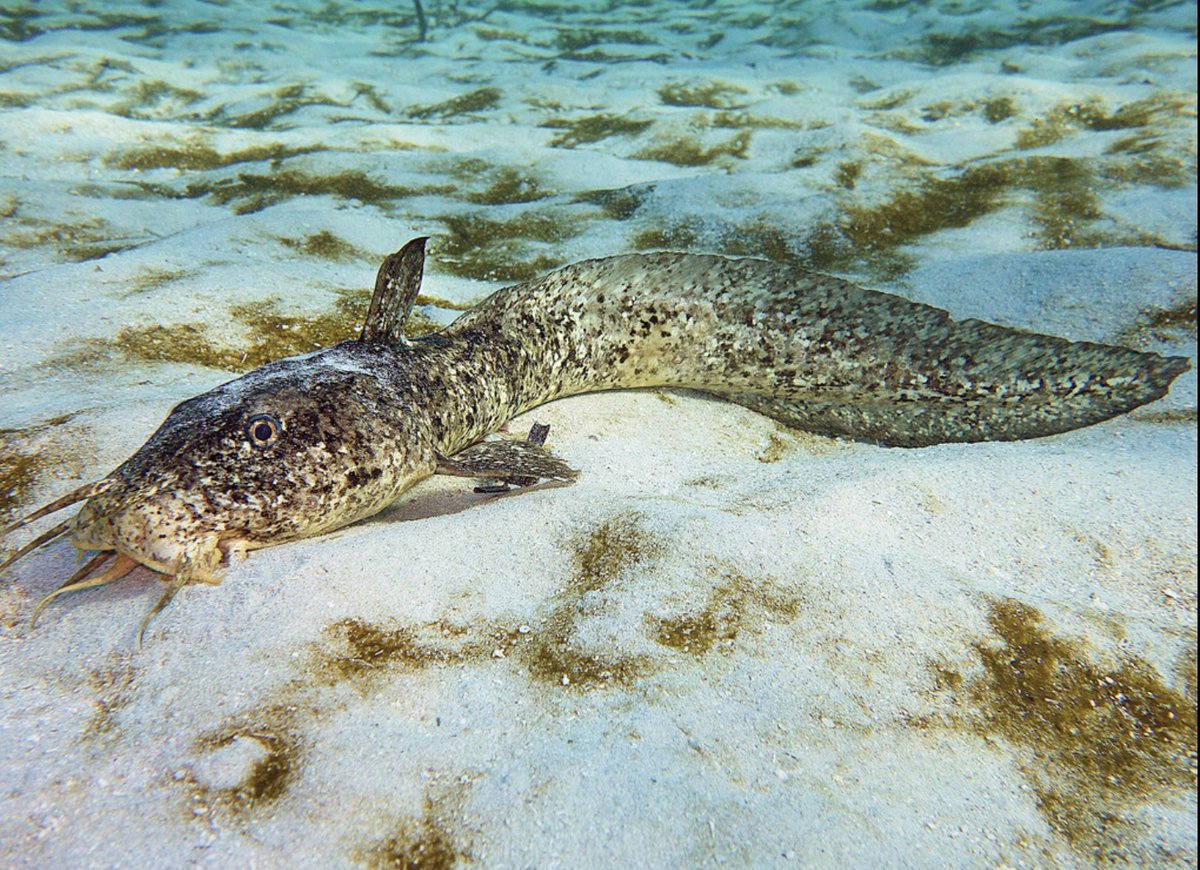

Like other drawings of its kind, this mon drawing is informed by an in-depth understanding of marine natural history. The fish known as inbeyaoyék in Biak is in English known as the eeltail catfish, a family of marine catfish called Plotosidae in Latin that are found throughout the Indian and Pacific Ocean. The dorsal fins of eeltail catfish are venomous, in some species like those of the striped eel tail catfish (which one often finds in the coral reefs of Raja Ampat) the venom is even lethal.

In the drawing, the flat head and the eel-like tail of the catfish are all clearly visible on the drawing. So, too, are the barbels, the long “whiskers” around the mouth that give the fish its English name. One begins to see, perhaps, why a sea witch might want to assume the form of this particular fish.

But there is more poison to this logic, still. I was told that tatóm, the algae tufts of hair that guard the sea witch in the drawing, occur more frequently in the season when the southeasterly wind predominates during the months between May and October. This observation that some magic might be seasonal in character is also based on good natural history observation. Tatóm is the filament-like and often poisonous cyanobacteria that goes by the Latin name Lyngbya majuscula. It is named after the Danish priest and botanist, Hans Christian Lyngbye (1782 – 1837), who was the first to describe them scientifically. Lyngbya majuscula are found in all oceans, but they are particularly at home in tropical and sub-tropical shoreline waters, where as Lyngbye noted, they only occur “at certain times of the year". When they bloom, Lyngbye also highlighted, they can cause seaweed dermatitis due to its toxin called lyngbyatoxin. Magic and natural history are sometimes toxic cousins (read more about queer toxins on the coral reefs of Raja Ampat).

Mon drawings, as I have begun to learn, tell entangled and interesting stories of meta-humans and animals, of political history and natural history, of life and death. The drawings have opened up an entirely new field of research for me at the intersection between marine biology, political history, and Indigenous knowledge. The drawings highlight to me that the coral reefs of Raja Ampat, famed for their rich marine biodiversity, are also rich in other forms of beings. These meta-human beings have histories that are at once natural, political, and magical. The mon drawings are teaching me to see coral reefs otherwise.